Euclid

| Euclid | |

|---|---|

Artist's depiction of Euclid

|

|

| Born | fl. 300 BC |

| Died | unknown |

| Residence | Alexandria, Egypt |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Known for | Euclidean geometry Euclid's Elements |

Euclid (pronounced /ˈjuːklɪd/ EWK-lid; Ancient Greek: Εὐκλείδης Eukleidēs), fl. 300 BC, also known as Euclid of Alexandria, was a Greek mathematician, often referred to as the "Father of Geometry." He was active in Alexandria during the reign of Ptolemy I (323–283 BC). His Elements is one of the most influential works in the history of mathematics, serving as the main textbook for teaching mathematics (especially geometry) from the time of its publication until the late 19th or early 20th century.[1][2][3] In the Elements, Euclid deduced the principles of what is now called Euclidean geometry from a small set of axioms. Euclid also wrote works on perspective, conic sections, spherical geometry, number theory and rigor.

"Euclid" is the anglicized version of the Greek name (Εὐκλείδης — Eukleídēs), meaning "Good Glory".

Contents |

Life

Little is known about Euclid's life, as there are only a handful of references to him. The date and place of Euclid's birth and the date and circumstances of his death are unknown, and only roughly estimated in proximity to contemporary figures mentioned in references. No likeness or description of Euclid's physical appearance made during his lifetime survived antiquity. Therefore, Euclid's depiction in works of art is the product of the artist's imagination.

The few historical references to Euclid were written centuries after he lived, by Proclus and Pappus of Alexandria.[4] Proclus introduces Euclid only briefly in his fifth-century Commentary on the Elements, as the author of Elements, that he was mentioned by Archimedes, and that when King Ptolemy asked if there was an easier path to learning geometry than Elements, Euclid replied, "Sire, there is no Royal Road to Geometry." Although the purported citation of Euclid by Archimedes has been judged to be an interpolation by later editors of his works, it is still believed that Euclid wrote his works before those of Archimedes.[5][6] In addition, the "royal road" anecdote is questionable since it is similar to a story told about Menaechmus and Alexander the Great.[7] In the only other key reference to Euclid, Pappus briefly mentioned in the fourth century that Apollonius "spent a very long time with the pupils of Euclid at Alexandria, and it was thus that he acquired such a scientific habit of thought."[8] It is further believed that Euclid may have studied at Plato's Academy in Athens.

Elements

Although many of the results in Elements originated with earlier mathematicians, one of Euclid's accomplishments was to present them in a single, logically coherent framework, making it easy to use and easy to reference, including a system of rigorous mathematical proofs that remains the basis of mathematics 23 centuries later.[10]

There is no mention of Euclid in the earliest remaining copies of the Elements, and most of the copies say they are "from the edition of Theon" or the "lectures of Theon",[11] while the text considered to be primary, held by the Vatican, mentions no author. The only reference that historians rely on of Euclid having written the Elements was from Proclus, who briefly in his Commentary on the Elements ascribes Euclid as its author.

Although best-known for its geometric results, the Elements also includes number theory. It considers the connection between perfect numbers and Mersenne primes, the infinitude of prime numbers, Euclid's lemma on factorization (which leads to the fundamental theorem of arithmetic on uniqueness of prime factorizations), and the Euclidean algorithm for finding the greatest common divisor of two numbers.

The geometrical system described in the Elements was long known simply as geometry, and was considered to be the only geometry possible. Today, however, that system is often referred to as Euclidean geometry to distinguish it from other so-called non-Euclidean geometries that mathematicians discovered in the 19th century.

Other works

In addition to the Elements, at least five works of Euclid have survived to the present day. They follow the same logical structure as Elements, with definitions and proved propositions.

- Data deals with the nature and implications of "given" information in geometrical problems; the subject matter is closely related to the first four books of the Elements.

- On Divisions of Figures, which survives only partially in Arabic translation, concerns the division of geometrical figures into two or more equal parts or into parts in given ratios. It is similar to a third century AD work by Heron of Alexandria.

- Catoptrics, which concerns the mathematical theory of mirrors, particularly the images formed in plane and spherical concave mirrors. The attribution to Euclid is doubtful. Its author may have been Theon of Alexandria.

- Phaenomena, a treatise on spherical astronomy, survives in Greek; it is quite similar to On the Moving Sphere by Autolycus of Pitane, who flourished around 310 BC.

- Optics is the earliest surviving Greek treatise on perspective. In its definitions Euclid follows the Platonic tradition that vision is caused by discrete rays which emanate from the eye. One important definition is the fourth: "Things seen under a greater angle appear greater, and those under a lesser angle less, while those under equal angles appear equal." In the 36 propositions that follow, Euclid relates the apparent size of an object to its distance from the eye and investigates the apparent shapes of cylinders and cones when viewed from different angles. Proposition 45 is interesting, proving that for any two unequal magnitudes, there is a point from which the two appear equal. Pappus believed these results to be important in astronomy and included Euclid's Optics, along with his Phaenomena, in the Little Astronomy, a compendium of smaller works to be studied before the Syntaxis (Almagest) of Claudius Ptolemy.

Other works are credibly attributed to Euclid, but have been lost.

- Conics was a work on conic sections that was later extended by Apollonius of Perga into his famous work on the subject. It is likely that the first four books of Apollonius's work come directly from Euclid. According to Pappus, "Apollonius, having completed Euclid's four books of conics and added four others, handed down eight volumes of conics." The Conics of Apollonius quickly supplanted the former work, and by the time of Pappus, Euclid's work was already lost.

- Porisms might have been an outgrowth of Euclid's work with conic sections, but the exact meaning of the title is controversial.

- Pseudaria, or Book of Fallacies, was an elementary text about errors in reasoning.

- Surface Loci concerned either loci (sets of points) on surfaces or loci which were themselves surfaces; under the latter interpretation, it has been hypothesized that the work might have dealt with quadric surfaces.

- Several works on mechanics are attributed to Euclid by Arabic sources. On the Heavy and the Light contains, in nine definitions and five propositions, Aristotelian notions of moving bodies and the concept of specific gravity. On the Balance treats the theory of the lever in a similarly Euclidean manner, containing one definition, two axioms, and four propositions. A third fragment, on the circles described by the ends of a moving lever, contains four propositions. These three works complement each other in such a way that it has been suggested that they are remnants of a single treatise on mechanics written by Euclid.

See also

- Axiomatic method

- Euclid's orchard

- Euclidean relation

Notes

- ↑ Ball, pp. 50–62.

- ↑ Boyer, pp. 100–19.

- ↑ Macardle, et al. (2008). Scientists: Extraordinary People Who Altered the Course of History. New York: Metro Books. g. 12.

- ↑ Joyce, David. Euclid. Clark University Department of Mathematics and Computer Science. [1]

- ↑ Morrow, Glen. A Commentary on the first book of Euclid's Elements

- ↑ Euclid of Alexandria. The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- ↑ Boyer, p. 1.

- ↑ Heath (1956), p. 2.

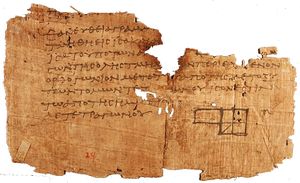

- ↑ Bill Casselman. "One of the Oldest Extant Diagrams from Euclid". University of British Columbia. http://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/Euclid/papyrus/papyrus.html. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ↑ Struik p. 51 ("their logical structure has influenced scientific thinking perhaps more than any other text in the world").

- ↑ Heath (1981), p. 360.

References

- "Euclid (Greek mathematician)". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2008. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/194880/Euclid. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- Artmann, Benno (1999). Euclid: The Creation of Mathematics. New York: Springer. ISBN 0387984232.

- Ball, W.W. Rouse (1960) [1908]. A Short Account of the History of Mathematics (4th ed.). Dover Publications. pp. 50–62. ISBN 0486206300.

- Boyer, Carl B. (1991). A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. ISBN 0471543977.

- Heath, Thomas (ed.) (1956) [1908]. The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements. 1. Dover Publications. ISBN 0486600882.

- Heath, Thomas L. (1908), "Euclid and the Traditions About Him", in Euclid, Elements (Thomas L. Heath, ed. 1908), 1:1–6, at Perseus Digital Library.

- Heath, Thomas L. (1981). A History of Greek Mathematics, 2 Vols. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486240738 / ISBN 0486240746.

- Kline, Morris (1980). Mathematics: The Loss of Certainty. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019502754X.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Euclid of Alexandria", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Euclid.html.

- Struik, Dirk J. (1967). A Concise History of Mathematics. Dover Publications. ISBN 486-60255-9.

External links

- Euclid's elements, All thirteen books, with interactive diagrams using Java. Clark University

- Euclid's elements, with the original Greek and an English translation on facing pages (includes PDF version for printing). University of Texas.

- Euclid's elements, All thirteen books, in several languages as Spanish, Catalan, English, German, Portuguese, Arabic, Italian, Russian and Chinese.

- Elementa Geometriae 1482, Venice. From Rare Book Room.

- Elementa 888 AD, Byzantine. From Rare Book Room.

- Euclid biography by Charlene Douglass With extensive bibliography.

- Texts on Ancient Mathematics and Mathematical Astronomy PDF scans (Note: many are very large files). Includes editions and translations of Euclid's Elements, Data, and Optica, Proclus's Commentary on Euclid, and other historical sources.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||